| MOMENTS OF TRUTH

I shot these photographs at the Spanish bullfights from 1956 to 1960. Ernest Hemingway attended a number of these corridas in the latter part of his life. Most often I saw him during the season at the Plaza Monumental in Madrid. The photos are intended to be abstracts of the events. I wanted to catch the motion and emotion of the event with a still camera. I processed the film to give me only black and whites and minimal grays. All shots were made from the stands with a 35-mm Edixa Reflex camera and a 50-mm lens. Shutter speed was always 1/25th of a second. The Panatomic-X film was underexposed and overdeveloped for contrast. The final subject on the postage stamp-sized negative was smaller than a fingernail paring from your pinky. Since the final prints are 8x10s, my enlarger to print distance was sometimes the length of a bedroom with timed exposures up to one hour and fifteen minutes long. I manipulated the focusing wheel on the enlarger at the other end of the room with strings, using a magnifying glass to focus sharply on the salt and pepper grain before I exposed the paper. The results speak for themselves.

Each Sunday at five o'clock in the afternoon, wearing the age-old traditional costume, this official always leads the procession into the ring at Madrid's Monumental Plaza de Toros.

Marching purposely out of step to the music, the matadors and their cuadrillas stroll behind in their glittering suits of light while the less important performers follow.

A trumpet signals the opening of "The Gate of Frights." Out roars a bull bred for bravery and ferocity. This animal associates man and horse as one because that is the only way he was ever allowed to see them on the ranch where he was raised.

In moments, using their large magenta capes, the cuadrilla must learn if a bull favors one horn or another, hooking right or left the way a fighter might use his fists.

The picador encourages the bull to charge his lance aimed to weaken the powerful neck muscle so that the bull might not jerk up its head and gore the matador during the last act. Sometimes, however, the bull gets the better of the picador, upsetting the man and his well-padded horse much to the approval of the crowd.

The placing of a pair of paper-colored darts or banderillas in the bull's neck muscle by another member of the cuadrilla is also to discourage the bull from lifting his horns as the matador leans over them during the final act.

The trick to placing the darts is for the running man and the charging bull to intersect at an angle. The man spins by inches from the horns as he places his darts. With a very fine bull some matadors break the dart shafts in two and place them themselves. This is rare but when it happens the crowd goes wild.

Numero Uno and his two cuadrilla members await their turn to perform. Each studies how the bull reacts so that their performance will not be a final one.

When things go well the man may pass the bull behind his back.

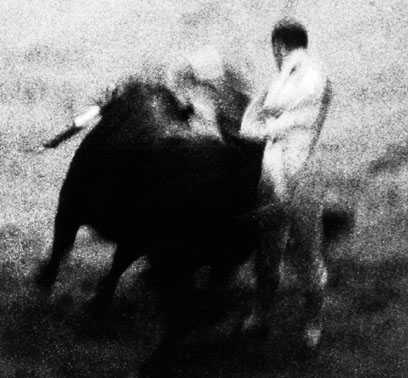

When things go badly, this can happen.

As well as this.

And this.

Or this.

And sometimes this, when the bull leaps out of the ring and a 65-year-old gate-keeper — still clenching his cigar — gets it. At the infirmary he told the surgeon, "He killed me." When they unbuckled his belt his stomach packet fell out. He was right.

And there is also this. It is rarely seen. It is called the Lighthouse Pass. Before the bull comes out the gate the man goes to media-arena, spreads his large magenta cape in front of him and kneels behind it. When the bull emerges, it charges full tilt toward the lone kneeling figure. One moment before impact, the man lifts the cape and swirls it around overhead, wrapping the charging bull around him.

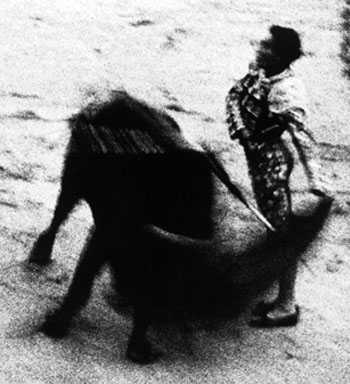

With the small red cape the matador works through his repertoire of passes, each time bringing the charging beast closer to him until it brushes him.

Ideally, the man plants both feet and only the cape and the bull move around him.

If the bull charges straight and true the man may show his bravery by gazing up at the crowd rather than at the sharp horn grazing his tunic with each charge.

When man and bull are very, very, good, at that moment they are immortal.

But then it is time for the final act. As he is about to take the sword the man knows this to be his final Moment of Truth. It must be swift, clean and perfect, or everything that has gone before is wasted.

His Moment of Truth is his moment of triumph as the stands erupt in "A Sea of White" waving handkerchiefs beseeching the President to award the matador all honors. At one fight the President waited until Hemingway pulled out his handkerchief and waved it, before he gave the matador his honors. The fans roared their approval.

This is Manolete. Hemingway never saw him fight. The crowd demanded that Manolete give them more and more spectacular performances. Finally, he did, on August 28, l947 in the bullring at Linares. In his final Moment of Truth, he gave them everything he had left to give. With the bull Islero, he killed while being killed. Many today believe Manolete was the finest of all bullfighters.

Hemingway once said that heaven to him would be a big bullring with him holding two ringside seats opposite a trout stream he alone was allowed to fish near two lovely townhouses, one for his wife and children and one with nine lovely mistresses, one on each floor. When I shot this picture of him in Pamplona he was quite close to his heaven. He had attractive young ladies at his shoulder most of the time (here he's talking to two of them) and each day he could go swimming and picnicking in a nearby trout stream. But best of all, he saw the bullfights daily. No wonder he looked and felt happy for his final Moment of Truth, his last Pamplona fiesta. He had fought the good fight. fini © 2001 Robert Forrest Burgess. All Rights Reserved. |

| return to Hemingway's Paris and Pamplona |